These South African Black Winemakers Are Reclaiming Stolen Legacies

Paul Siguqa stood at the podium, looking out at the sea of people waiting to hear him speak. There was barely any standing room in the conference hall—organizers struggled to fit in as many guests as possible. They had underestimated, not expecting such a turnout for this, the first afternoon seminar at Cape Wine’s 2022 exhibition. People—eager to learn about the shift occurring in South Africa’s wine industry and how Black people were leading the transformation—turned out in droves.

Siguqa, the son of a farm laborer, gave an impassioned speech about changing the narrative long bestowed on Black farmers in South Africa. He talked about land ownership, diversifying the value chain and the benefits a more inclusive wine industry could bring for the country’s entire economic landscape.

“If it’s possible for a child of a farm laborer to become a farm owner, then it’s possible for a child of a domestic worker to become a doctor, a scientist—you name it,” he told the crowd.

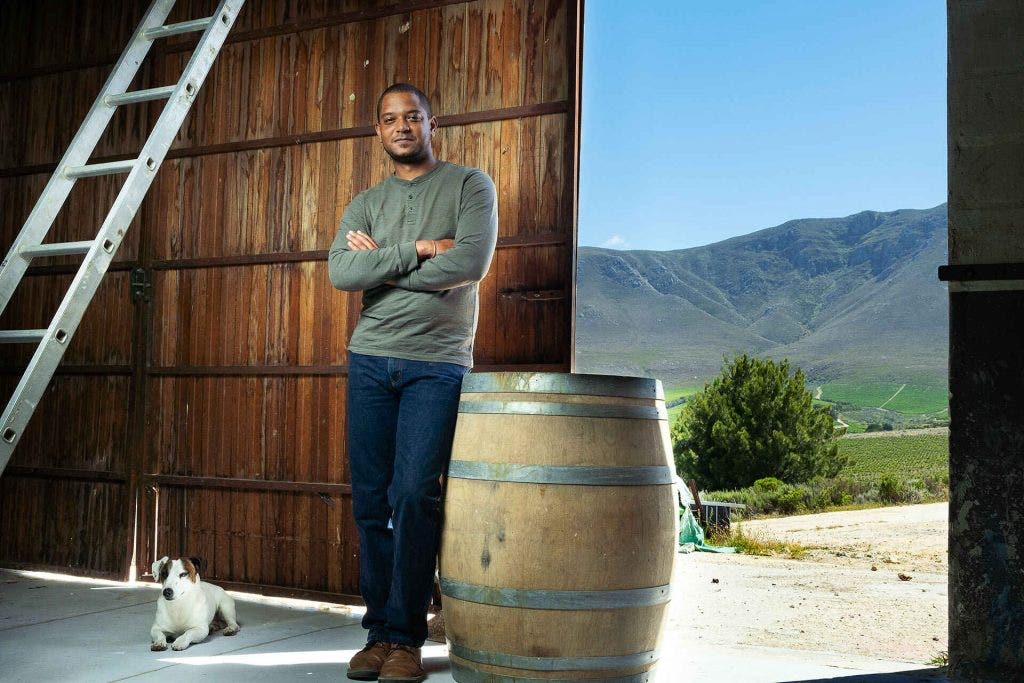

Siguqa is the owner of Klein Goederust, a nearly 100-year-old brand his family acquired in 2019 and the first and only 100% Black-owned and -operated vineyard and winery in South Africa. Despite only entering the industry a relatively short time ago, he’s already shown that Black farmers and winemakers can be quite a good thing for wine tourism. Since opening day in 2021, drinkers of all backgrounds have flocked to his winery in Franschhoek to try Klein Goederust’s Cap Classic, Cabernet Sauvignon and Chenin Blanc.

Speaking via Zoom two months after his speech, Siguqa doubled down on the many advantages that could arrive from having more Black people involved in South Africa’s wine business. His comments come at a time when the country is facing political and economic turmoil, with wealth and poverty disparities among Blacks and whites as wide as they were when apartheid’s racial caste system was dismantled almost three decades ago.

Black South Africans currently comprise more than 80% of the population, while whites only account for about 8%—however, according to a 2022 New York Times report, whites own 79% of privately held farmlands. Siguqa, a staunch advocate for land ownership, believes if more Black people were able to purchase and develop their land, “the wine industry in our country can grow and expand far beyond what’s already been achieved.”

Siguqa’s interest in reshaping the wine industry is a surprise, considering he grew up detesting wine and everything that came with it. Raised in the Franschhoek Valley, Siguqa watched his mother perform grueling labor at vineyards for incredibly little money, sometimes only receiving jugs of wine as payment under South Africa’s former dop system—though officially abolished in the 1960s, this method of paying workers with wine persisted into the 1990s.

“The winelands weren’t a prestigious place for Black people, because when I was growing up, all you could be there was a farm laborer. There were no other options,” Siguqa says.

Siguqa’s perspective changed when he got a job serving wine at a tasting room while putting himself through college. There, he got the idea to own a winery after noticing more Black people coming to enjoy wine.

A successful businessman, Siguqa spent 15 years running a communications and events company and saving every penny he made before he finally bought a plot of land in 2019 just 10 miles away from where he grew up in Franschhoek. He tapped Rodney Zimba, whose parents worked at the same vineyard as Siguqa’s mother, to serve as his head winemaker.

“Rodney knew this was bigger than both of us because it changes the narrative of our people. It also shows that Black people can farm here and make wine, and we can do it successfully. He believed in the vision and was willing to work with me to create that narrative,” Siguqa says.

Pulling Teeth

The notion of working to the bone isn’t lost on any winemaker of color trying to get ahead in South Africa’s wine industry, especially Carmen Stevens.

Since embarking on a career as a winemaker more than 20 years ago, Stevens has worked tirelessly to prove that Black South Africans can be more than just farmhands. Through her namesake label, she intends to show that Black people are also good at making quality wine.

“Now it’s fantastic to take a Black winemaker on in your company. It’s part of corporate social investment, which the government says companies must do. So Black people are being pulled in, today. But in the ’90s, for a young Black woman, a child of a factory worker who grew up during apartheid, it wasn’t like that,” Stevens says. “It was always like, ‘Know your place and do your job.’ I had to work to prove my worth over and over.”

Having become the first Black person admitted to Elsenburg Agricultural College to study winemaking in 1993—only after being denied three separate times because of her skin color—Stevens was already something of a pioneer in South Africa’s wine industry. During her years at Distell, she made white wine for Zonnebloem and later served as head winemaker for Tukula, a brand Distell created as part of its Black empowerment project.

She spent a harvest working in the vineyard and the cellar at Simi Winery in Sonoma, California (itself a pioneer in female-led wineries), after which she landed winemaker roles back in South Africa at Welmoed Winery and Amani Vineyards. In 2011, she launched her Carmen Stevens Wines label through Naked Wines, and in 2019, she took complete control of her brand and became the first Black woman to open a winery in the esteemed Stellenbosch wine region, where she produces award-winning bottles of Sauvignon Blanc, Merlot, Petite Sirah and Carménère, among other varieties.

But this success hasn’t come without challenges and doubters.

“Access to the market is like pulling teeth. There’s a stigma about Black winemakers. People always mention the quality of the wines and ask, ‘Can the wines really be that good?’ But when they finally come in and try them, they’re impressed with what we make,” Stevens says.

Both Siguqa’s and Stevens’ wineries employ a small team of Black winemakers and interns, with whom they happily share their knowledge. Serving as mentors and encouraging the next generation in wine is incredibly important. Their efforts couldn’t come at a more critical time as the outlook on Black people and what they can do with wine is starting to change. Meanwhile, even more young Black people are entering the industry, hoping to share a different story of South African wine.

An Untold Story

“I wanted to make something unique to South Africa because I understood that many people are prejudiced against African wines. They turn their nose when they see it’s an African wine,” says Rüdger van Wyk, winner of the 2018 Diners Club Young Winemaker of the Year and head winemaker at Stark-Condé. “So, I wanted to create something beautiful and unique that could show the best of where I’m from, all while sharing a bit of my culture and upbringing.”

Van Wyk is the owner of Stellenbosch-based Kara-Tara, a label focusing on Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, which he named after the iron-rich river that flows through the small logging town of George, where he grew up on the southeast coast of South Africa.

A Stellenbosch University graduate, van Wyk is also a former student of the Cape Winemakers Guild Protégé Programme, which provides mentorship for young wine professionals and has helped over 30 protégés complete internships and land positions at top wineries. Though van Wyk only completed one year of the three-year program, he says having access to such an esteemed organization played a crucial role in where he is today.

“I learned a ton and gained a lot of experience. I was able to work at great farms, and I even went to Burgundy. Few people get to go there and help make wine, especially Black people,” van Wyk says. “I had a ball of a time there, and that trip really shaped my winemaking philosophy and the type of wines I wanted to make for Kara-Tara.”

For van Wyk, making wine and launching his own label is a chance to tell an untold story and to change perceptions. It’s about passing on the essential lessons his parents instilled in him, like the importance of giving, creating a legacy and using the examples of those before him to set an even higher standard for those who will come after.

“It’s all about reinvesting the knowledge and experience that you gained. I don’t know too much about what life is. But what I do know, I want to share because sharing our knowledge and experience to help people change their situations can be a benefit in changing the country for the better overall,” van Wyk says.

What’s the Benefit?

At Brunia Wines in Sondagskloof, within the Cape South Coast, Wade Sander is taking that information-sharing exchange to the next level. While the Johannesburg-born winemaker focuses on creating high-quality Pinot Noir, Sémillon and Syrah, his family-owned organic and biodynamic farm focuses on sustainability with an emphasis on social responsibility.

“We have legacy farm workers in the Western Cape and social ills that have come with that—ill treatment from farm owners and land owners, evictions of Black farm workers, people not having access to the land they’ve worked their entire lives. We wanted to get past that because we knew if we were successful and the people we worked with were successful, then that would be the best situation to take us all forward,” says Sander.

A former Cape Winemakers Guild Protégé and Elsenburg graduate, Sander completed harvests in California’s Edna Valley and worked with Thierry Germain of Domaine De Roche Neuves in France’s Loire Valley before joining the winemaking team at Mullineux & Leeu Family Wines in 2015.

When Sander’s parents approached him and his brother about potentially purchasing property and starting a family farm, he seized the idea of making wines that could show their perspective of what sustainable South African wine could be. In 2016, the family purchased Cold Mountain Vineyards, creating a multi-enterprise farm, growing fig trees, seasonal vegetables and the grapes used to make Brunia’s wines. They also launched the Cold Mountain Farm Cooperative, giving families who had worked the land for generations the opportunity to not only remain there but also to buy into Brunia and develop generational wealth for themselves.

“We want a deeper relationship with our employees. I believe there is a greater benefit of the business if we have people that grew up on the land work with us, lease the areas they live on, and farm for themselves,” Sander says.

He asks, “What’s the benefit of being a Black-owned brand when you can only buy grapes from white farmers? When you’re paying them to make wine in their cellars? How much real investment are you making into our community?” letting the questions hang there a moment. “That’s something that’s become extremely important to us.”

This article originally appeared in the April 2023 issue of Wine Enthusiast magazine. Click here to subscribe today!